Everyone wears masks in a way, presenting slightly different versions of themselves in different public situations (perhaps to “unmask” only at home). But gender dysphoria is like a cursed mask melded with your face, an undesirable deception that is overly tight and non-removable (without the right magic spell).

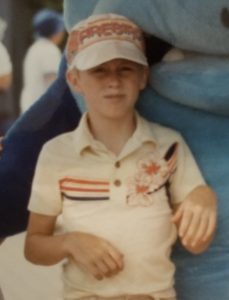

I think that as young children, we tend to accept what the adults around us say, uncritically & regardless of how it feels. For me, in the faint wisps I can recall of my childhood, I was indifferent to the label of “boy” and its trappings (including my boy-name); I didn’t mind it, but neither did I “identify” as it – it was just one of those things people said to/about me. (That said, I insisted on nail polish as a toddler & makeup was generally required each Halloween.)

My indifference began to shift into conflict after enrolling in Catholic school (grades 7-12), which had gender-specific dress codes. At first, it was fun, like a weird costume party all the time, wearing a tie like some “businessman,” but it didn’t take long to feel oppressive. I noticed the girls’ dress code had a lot more flexibility. Girls could have any hair length, wear several different styles of shirts with skirts, Capri pants or regular pants, but boys hair must be short and they could only wear full-length, solid color slacks with button-up shirts and ties.

I grew deeply envious of the freedom the girls had with their appearance, even though I had no thought of wearing skirts. In high school, I got into 1970’s rock and began to think of myself as a “Romantic” (pseudo-hippy / poet) and fantasized about wearing billowing Renaissance-style “men’s” blouses and colorful pants paired with long, flowing hair. I loved reading fantasy novels, especially when the heroes were men (or elves) with long hair (or on the rare occasion, women). Our “hair above the collar” boys dress code put a stop to any long-hair plans (which could only be indulged over summer break).

I became friends with a variety of boys and girls, but preferred talking to girl-friends because they were more interested in stories and would talk about “real” things like emotions, whereas the boys I knew communicated mostly in terms of jokes and music. However, I felt increasingly oppressed / distressed (by puberty and the “gender police,” including a few bullies and gender segregation, but with the dress code being my standout enemy).

When I became friends with a bunch of theater kids, they helped my misfit tendencies to flourish. One of them had discovered a secret way to grow his hair out (he hid the growth pinned inside itself like an inverted ponytail). After my 16th birthday, I started growing my hair also, planning to use the same trick. By June, several of us boys had “longish” hair and we made a pact to mess with people by wearing pigtails on the last day of school. I was very self-conscious, but also proud to sport my pigtails. It lasted less than an hour; after homeroom, on my way to 1st period, the burly vice principal / monk pounded down the hall after me and screamed in my face to TAKE THEM OUT NOW!

I was humiliated and devastated. That was only the slightest feminine presentation (as a “joke”) and it was met with utmost hostility. Since school was over for the summer, I decided to keep growing my hair anyway, despite the futility. Towards the end of that summer, I sank into a deep depression, dreading the day I had to cut my hair and go back to my school and its dress code. It’s hard to describe how deeply despairing / panicked / trapped I felt – let’s return to the cursed mask analogy; I was trying desperately to lift the mask just a little, but it was stuck fast. Gender dysphoria.

My fairy godmother (aka bio-mom) worked some magic, though – I never went back to that school. Instead, I skipped my senior year and went straight to college where I drank the elixir of relative freedom. Long hair and long fingernails were a happy relief at first, then some hair colors (starting green, then purple), then a friend introduced me to nail polish and I was like, “oh!” I became friends with a small group of goths* on campus and it wasn’t long before I was experimenting with a bit of makeup (plus nail polish) and eventually bought my first skirt. I didn’t yet think of it in terms of gender, though, I just thought I was anti-conformist.

*Goths, for those who don’t know, were members of the “gothic” subculture which evolved from the New Romantic and Punk Rock music scenes in the late 1970s and which saw a resurgence in the mid-1990s, when it caught my attention. Androgyny and vampiric looks (and sounds) were a key feature; most wore all-black.

The battles came when I had to leave my idyllic liberal arts campus for “the real world” on breaks – would I tone it way down to get along or be myself and get hassled? I had some epic fights with hostile family members – take it off, take it off now, they yelled, just like my vice principal. And the more supportive family members warned me about getting attacked or murdered if I went out in public like that (for my own protection, they argued, I should tone it down). I felt like I was put in shackles every time I was on break from school.

After transferring to a different, larger college to pursue my chosen degree, I went full out. I had accumulated a small wardrobe of goth / genderqueer clothing, cheap black eyeliner and (not so cheap) dark lipstick. I wore skirts often, even walking past fraternity row. I experienced a near-constant stream of gender- and sexuality-related insults and comments walking around certain areas (e.g., the aforementioned frat row). It took a few months, but I made friends with a handful of goths and other outliers there. I wasn’t really comfortable around masculinity anymore, preferring to befriend girls or boys who were at least a little feminine (fortunately, common traits among goths).

I hit another dress code snag at the start of my junior year, as it dawned on me how conservative my chosen field (environmental engineering) was going to be – shorts might be OK for field samples, but this was a “preppy” profession where my quirks would not be welcome. I also lost interest in the content of my education as I realized the jobs were going to be mostly corporations self-policing to minimalist standards and not the significant positive changes I had envisioned. I decided I wanted to pursue a more creative path in a more diverse city, but when I floated options for switching major/schools to my parents (who were supporting me), they said absolutely not.

The summer before, I had developed an intense hatred for my body, my worst dysphoria yet, which was now mixed with abject hopelessness regarding my future. This depression was very bad. I cut way back on food, socializing and attending core classes; I barely managed to go to my part-time job and my favorite class (an elective: metalsmithing).

I was always told to persevere and finish what was started, but that prospect was devastating. Eventually, in desperation, I had a revelation – I could just quit; I could leave school and move away. Allowing for this possibility lessened my depression enough to become functional for planning my exit strategy.

I finished the semester, managing to pass a few classes (those I hadn’t dropped) and saved money from working until I could afford to move to the city where some friends offered to rent me a room (friends I’d met the previous summer at a giant goth festival). When I got there, I felt huge relief, being away from dead-end school and parental arguments.

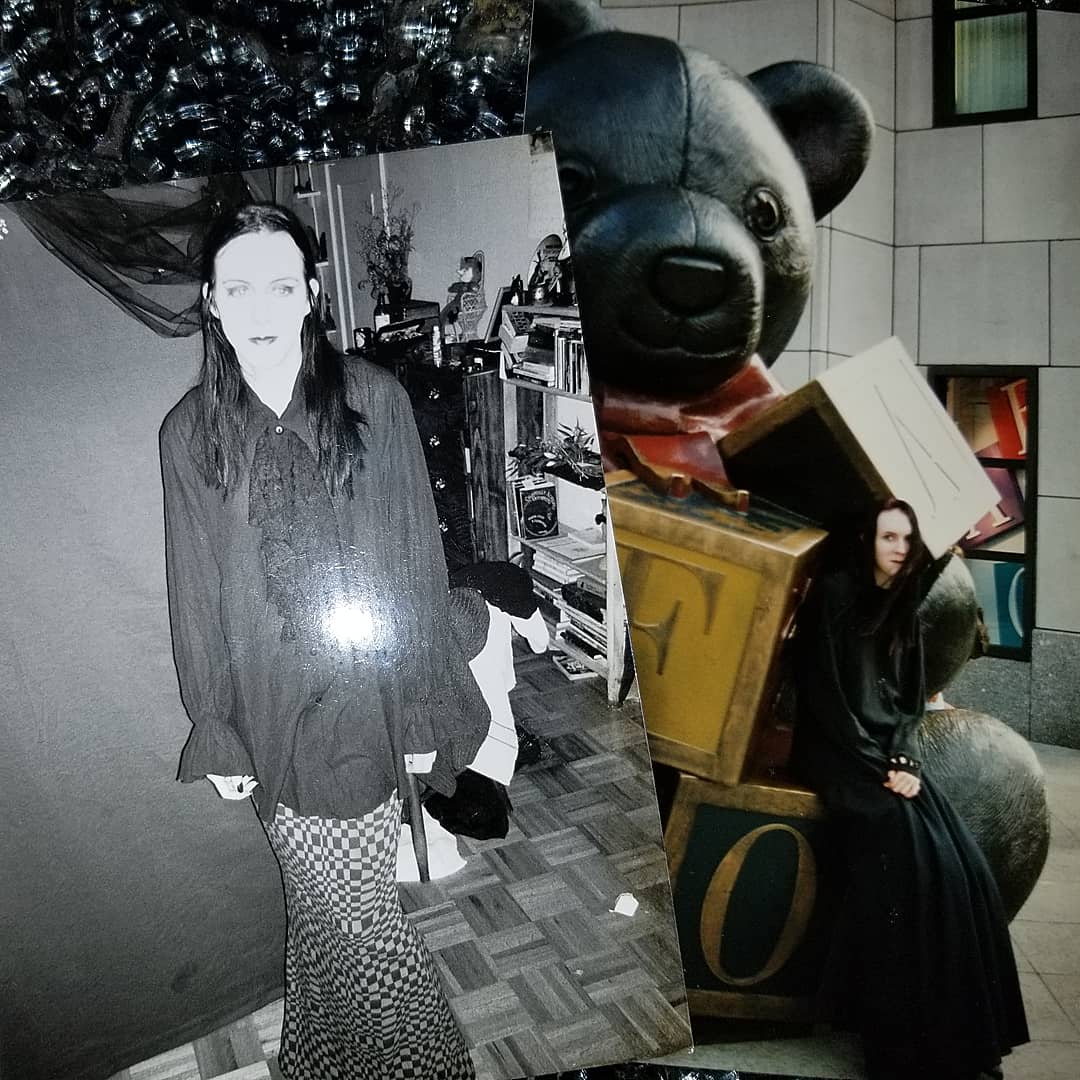

More importantly, I now had a larger community where I could really be myself, the goth clubs we attended twice weekly, where creative and androgynous attire was strongly encouraged and I could dance (how I loved to dance). Many of our favorite bands/songs featured male-born figures wearing makeup, dresses and other feminine attire. People outside the scene would call me a “crossdresser,” but I never liked that term – I wasn’t “crossing” anything, I was just expressing my true self.

However, the move came with new gender challenges. After a month of fruitless job searching and running low on my savings, I realized that in order to get a full-time job, I needed “normal” hair, so I dyed my multi-hued hair solid black. I got hired as a temp secretary in an office, so I began wearing button-up shirt, tie and slacks, back to the “businessman” costume, but at least with long hair (neatly back in a ponytail). Awful, but I figured it’s normal to hate going to work – it’s not play, after all. I got to dress up as “me” on the weekend when I went to the clubs or hung out with friends (as pictured).

I grew to love aspects of my job after I got moved to a different floor and was added to a “pool” of secretaries. Even though I wore masculine clothing, I got to be “one of the girls” in a way, as we all covered for each other (on breaks), gossiped about/with our coworkers, and a few of us even read or discussed Women’s magazines (like Cosmopolitan) on the sly or engaged in personal email correspondence (I had a bunch of friends in different cities). And there were always slow times as a secretary, especially if you were a fast typist like me (thanks to 3 different typing classes I had taken as a kid). Plus my bosses were women, which was cool.

As a club kid (starting around age 19), many/most of my friends called me by feminine versions of my name or the special androgynous moniker LGQB (Lord God Queen Bitch), which I liked. I never specified a nickname (although I spelled my name non-traditionally), they just naturally did that. In the club world, I received acceptance and appreciation for how I dressed and wore makeup. At work, I retained my legal name, which went along with my “man costume” (performative for the corporate world).

It wasn’t until I went back to college (this time for a computer and art major and paying my own way) that I discovered gender studies and began to seriously think about this stuff. I came to consider myself “transgender,” but came to realize that many people (mis)understood that term as applying only to “transsexuals” which I didn’t feel that I was. I wasn’t depressed, but completely preoccupied with figuring out my gender identity (which I now realized was separate from my goth persona) – neither boy nor girl and unable to articulate it.

People (other than my close friends) would frequently ask me if I was gay, even confrontationally at times. I had lots of gay friends and I knew that didn’t describe my experience. I’d find myself trying to explain the difference between sexual orientation and gender orientation, to limited effect – most everyone believed that gender was simple, binary and assigned at birth. Then they would ask me if I wanted to be a woman; I’d usually respond with a dismissive laugh and state that I definitely didn’t want a period (sorry, bio-women).

I couldn’t even figure out what pronouns I wanted – I told the few really supportive people who asked to use a mix of she and he. I tolerated the “always-he” from most everyone else (other than those strangers who saw me at my most feminine and read me as “she”). Honestly, both felt fake to me; “he” felt fake with who I was internally and “she” felt fake externally because I didn’t “pass” and wasn’t planning to take hormones nor transition. Sometimes I’d say I was 60% feminine, 40% masculine.

FYI: my current preferred pronouns are they/them.

I began wanting to change my name as I thought this would eliminate some of the gender confusion, but didn’t come up with any brilliant ideas worth the hassle, so I tabled it. This was just before the turn of the century and transsexuals were just starting to become more widely known (but definitely not accepted); the whole concept of “non-binary” or “genderqueer” was alien to just about everyone, including feminists, academics and even some of my goth friends who were boys wearing makeup (who nevertheless identified firmly as “men”). It was very frustrating, being not exactly invisible, but maybe more “unseeable”? I was lucky, in a way, because this was a terrible time for queer people and I’m certain there are times I could’ve been attacked, but usually anyone hostile who encountered me was too confused to take action, they’d rather just “unsee” it. But it was also heartbreaking to be “just a man in a dress” to people who knew me, even loved me.

For my senior capstone project, I decided to do something on my non-gender gender. After months of research, brainstorming and materials creation, I completed my project (called, “GenDissent”), which was both a thesis paper and a multi-media art installation. My parents, local friends and my long-distance girlfriend attended, along with my EMAC classmates and teachers. It was, in a way, a public coming out. I’m not sure everyone understood it, but at least I’d expressed it. It felt good. I felt done.

Months and another move later, a new girlfriend would often exclaim, “Isn’t he pretty?!” when introducing me to her friends at the nightclubs. I thought it was cute at the time, but when she broke up with me without any kind of fight or incident and I asked why, she admitted I was too feminine (mentally, I bristled, ‘I was wearing a dress when you met me!’).

I wasn’t too bothered by the end of that not-serious relationship, but despite what I’d thought of as my clarity of gender expression, I now knew I was still subject to serious misunderstanding; cultural indoctrination was not going to be easily overcome. People, compassionate or not, would still perceive “man in a dress” because they believe gender is binary and biological.

– – – – –

Fast-forward a few decades and “non-binary” has momentum (especially with the young queer community), so much so that there’s even a new goofy slur, “transtrender.” I’ve got a new name, different hair, better makeup skills, but still clash with mainstream entrenched ideas of gender (& getting people to stop calling me “he”). I guess gender expression for us outliers is a Lara Croft style journey, filled with helicopter crashes, lost luggage, precarious climbs, wardrobe upgrades, hostile fanatics and occasional treasure. ¯\_(‘_’)_/¯